Research Review

Jun et al. Chiropractic & Manual Therapies (2020) 28:15

Potential mechanisms for lumbar spinal stiffness change following spinal manipulative therapy: a scoping review

Abstract

Introduction: In individuals having low back pain, the application of spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) has been shown to reduce spinal stiffness in those who report improvements in post-SMT disability. The underlying mechanism for this rapid change in stiffness is not understood presently. As clinicians and patients may benefit from a better understanding of this mechanism in terms of optimizing care delivery, the objective of this scoping review of current literature was to identify if potential mechanisms that explain this clinical response have been previously described or could be elucidated from existing data.

Methods: Three literature databases were systematically searched (MEDLINE, CINAHL, and PubMed). Our search terms included subject headings and keywords relevant to SMT, spinal stiffness, lumbar spine, and mechanism.

Inclusion criteria for candidate studies were publication in English, quantification of lumbar spinal stiffness before and after SMT, and publication between January 2000 and June 2019.

Results: The search identified 1931 articles. Of these studies, 10 were included following the application of the inclusion criteria. From these articles, 7 themes were identified with respect to potential mechanisms described or derived from data: 1) change in muscle activity; 2) increase in mobility; 3) decrease in pain; 4) increase in pressure pain threshold; 5) change in spinal tissue behavior; 6) change in the central nervous system or reflex pathways; and 7) correction of a vertebral dysfunction.

Conclusions: This scoping review identified 7 themes put forward by authors to explain changes in spinal stiffness following SMT. Unfortunately, none of the studies provided data which would support the promotion of one theme over another. As a result, this review suggests a need to develop a theoretical framework to explain rapid biomechanical changes following SMT to guide and prioritize future investigations in this important clinical area.

What does this mean and why is this important?

We know spinal manipulation typically produces short term transient positive outcomes, i.e. the patient feels better for a bit and then slips back a bit. We also know that spinal manipulation to low back reduces spinal stiffness, but what we do not know is why this reduction in spinal stiffness occurs and this is what this study tries to identify. This scoping review combines several studies which have tried to identify the ‘why’ however despite identifying common themes the quality of the evidence is not high enough to consider one over another.

What does this mean in clinic?

One of the most common questions we are asked is ‘how does manipulation work?’ and despite a lot of studies trying to identify this there is not the quality of evidence to identify a specific mechanism of action for spinal manipulative therapy. Despite this we know that it does provide positive outcomes for patients when used as part of a comprehensive package of care.

You may also like..

Running Biomechanics

Over the past couple of years I have completed 2 running biomechanics and injury courses, one from a reductionist perspective and one from an optimist’s perspective. The reductionist perspective is that everybody needs to fit in a certain box, we all need to run with a certain style or form, there are specific que’s to give the individual to correct their erroneous ways to adapt the most effective running technique. We need to keep the knee over the foot and hip over the knee etc.

The optimist on the other hand was all about the person having their own running style and working with them to improve their ‘efficiency’ in their style, and I can see the reasoning in this when you watch a local race and see how individual running styles can vary. Both standpoints are valid, however when we look at the picture above we can see that Mo Farah is collapsing into valgus (knee dropping in) on the right, which, if we approached this from a reductionist perspective, would need correcting for Mo to run more efficiently, and here lies the problem, if we were going to try and correct this what impact would this have on his performance? Initially probably a negative one, so at this end of the performance spectrum would we want to do this? Probably not, most likely because he is highly adapted to his running form and maintains a high training volume without pain or injury. However, if we introduce pain to the mix, let’s say pain around the knee, should we try to correct, again my feeling about this relates to another blog ‘play what is in front of you’.

In a highly trained athlete, the chances are we would not be able to and the athlete would be reluctant to change anything, but that doesn’t mean that we wouldn’t try to ‘change the load’ through the knee by giving some strength work through the hip or playing with his cadence (in short term) so that he can keep running. At the other end of the spectrum with an individual who is new to running, would we try to correct this if they are suffering from knee pain?

One thing which is commonly observed with new runners is that their cadence (steps per minute) is low so it might be that increasing the cadence is enough to change the load on the knee and reduce the symptoms to allow them to continue running, however giving them relevant hip ‘strength’ work would also enable them to hold their ‘form’ for longer and thus increase the size of their engine and to be able to run further and quicker while reducing injury risk.

You may also like..

Play what is in front of you!

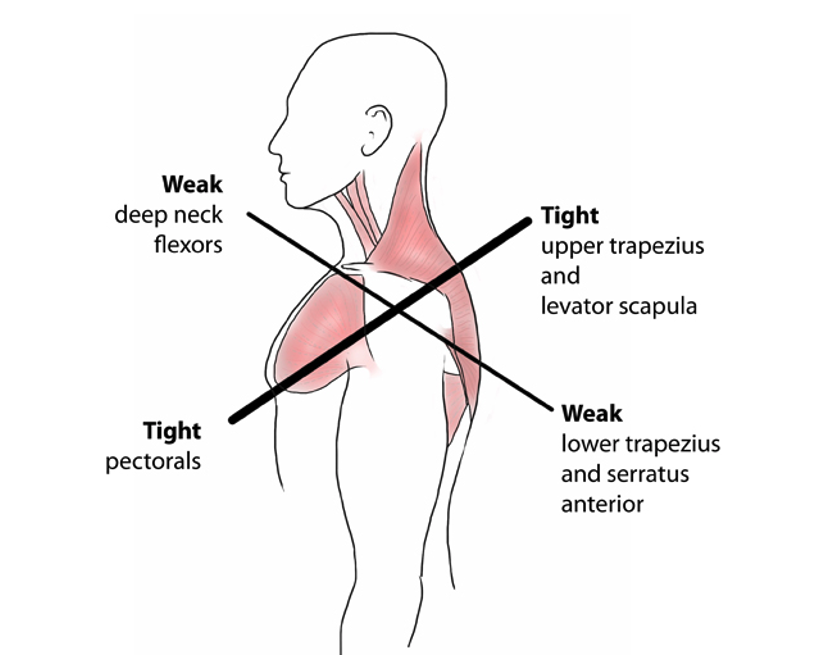

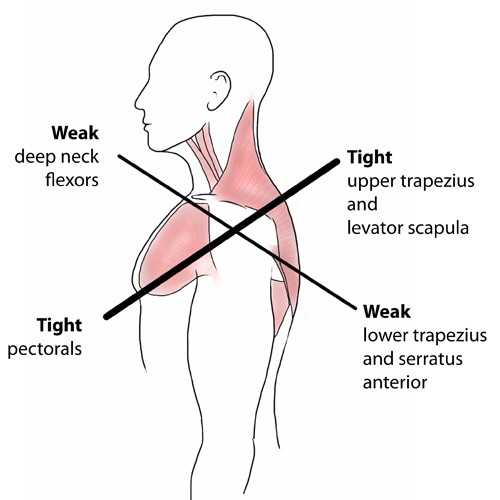

Having played rugby league for nearly 20 years to a reasonable standard and having played a good portion of that in a decision making the role of halfback there are a number of things which have stuck with me, one of the more prominent sayings that were impressed upon us was to ‘play what is in front of you’. What is meant by this is that when you are attacking with ball in hand you need to make the right decision or pick the right pass depending on what the defence is doing in front of you. How does this apply to the clinic? Well if we consider a team who play with a lot of structure to their attack, using all pre-determined plays i.e. we go from A to B to C, the game becomes very cookbook and it is the same with clinic, if a patient presents with X we do Y and Z to get the desired outcome, this works well when we are dealing with a standardised form, however like a opposition defences are unpredictable, patients rarely fit that clearly defined clinical picture which we were taught at university. For example we were taught at university that there was a condition related to posture called upper crossed syndrome (see image), in the 8 or so years that I have been out in the real world I have rarely if ever seen this complete syndrome, have I seen components of it? Yes, was it relevant to the patient’s complaint? Sometimes. Sometimes it needs to be dealt with and others it can be left and the patient will get on just fine leaving it, because to change it would mean altering posture, and posture often comes back to the most energy-efficient and comfortable position for that individual, so we need to play what it is in front of us i.e. the patient and make clinical decisions as to whether something is relevant or not.

You may also like..

The Joint by joint approach, victims and villains

This approach basically suggests that as we move we need certain joints to be stable while others are mobile. From the bottom up, we need a stable foot, mobile ankle, stable knee, mobile hip, stable lumbar spine, mobile thoracic spine (rib cage), stable neck and shoulder blade, mobile shoulder joint and so on down through the elbow, wrist and hand. This stands to reason in my eyes when we look at the anatomy of the joints, if we look at the knee, it is basically a big hinge, which moves predominantly through flexion and extension, although we can develop some small degree’s rotation in it. In comparison consider the hip, which is a ball and socket joint, the very nature of the ‘ball’ at the top of thigh bone should give an indication that the joint should move in multiple directions, which a healthy hip joint can quite happily do!

This approach to movement is quite relevant in today’s society. People are sitting for longer periods of time, what this leads to is joints which should be mobile becoming stiff, the ankle, hip and thoracic spine, while we then ask more of joints which should be stable, the foot, the knee and the lumbar spine. This is where victims and villains come into it, the site of the pain is not where the problem is. Take for example the knee, non-traumatic knee pain, patella-femoral pain syndrome or ilio-tibial band pain, very rarely is problem in the knee, it is just the victim of altered joint function either above it at the hip or below it at the ankle and foot, either one or both being the villain! So we could try and treat the knee, hopefully get some symptomatic relief, or we could look at the bigger picture, working out where the villain is and correcting that painless dysfunction which will then help the ‘stabilise’ the knee in the long run.

The Spine

Many people will experience back pain of some description at some point during their life, for this reason I have chosen to right a quick blog about the anatomy of the spine and various pain generators within. This should help people better understand the range and possible causes of their back pain. In its most basic description the spine is made up of blocks of bone, known as vertebrae, stacked on top of each other, with the head at the top and pelvis at the bottom.

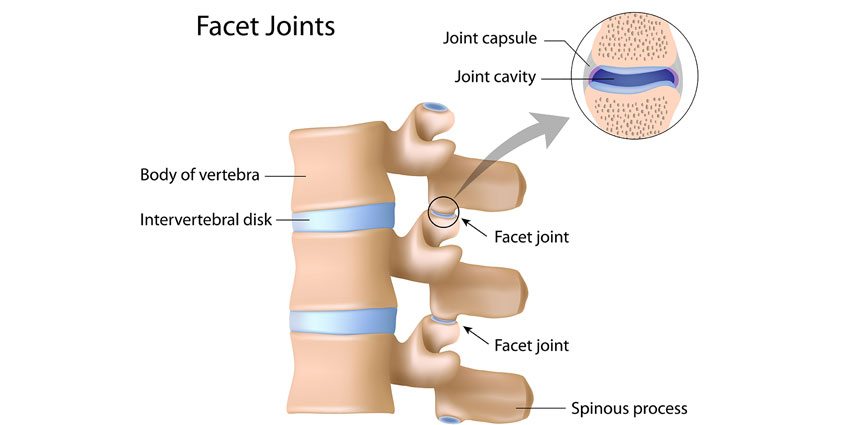

The Facet Joint

The facet joints make up part of the three joint complex which governs movement in each motion segment of the spine. This three joint complex is made up of the intervetebral disc (IVD) and the posteriorly positioned facet joints, one left and one right. For an overview of spinal anatomy please view my earlier blog The Spine. (link).

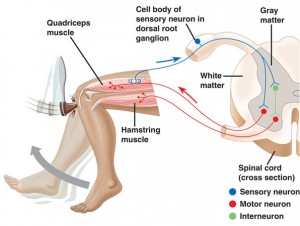

Peripheral Neurology

Many people present to the clinic complaining of both a central problem, e.g. low back, and a peripheral problem, e.g. leg pain, with many presuming the cases are linked together, in this scenario via the sciatic nerve. However, sciatica is one of the most commonly mis-diagnosed symptoms seen in practice, after all ‘true’ sciatica is symptom that something is going on closer to the central nervous system.